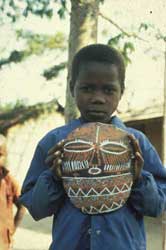

|

|

Dogon peoples, Mali Every few years the Dogon peoples honor their dead in a very religious performance and ritual called a dama. It is a joyous occasion because Dogon peoples celebrate a person's life rather than the sadness of his death.Although children do not wear masks, they imitate the movements of the adult masqueraders. This helps them learn the masquerades they will perform when they are older. The leaf masquerade is a child's masquerade. It must be performed before adult masquerades that celebrate the planting season. Farmers cannot plant their fields until the leaf masquerade is performed. |

|

The leaf masquerade is a child's masquerade that marks the change of the seasons. Boys wearing leaves represent the wildness and danger of the bush. Boys without masks are musicians, helpers or members of the audience. |

Boys are not allowed to participate in dama masquerades, but they sometimes make toy masks. Disguised in their masks, they run on to the dancing ground before the adults appear, dance for a few moments and quickly run away. |

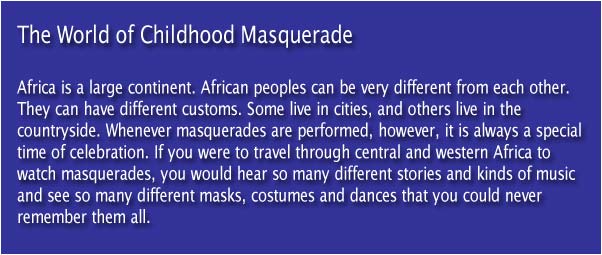

Okpella peoples, Nigeria The Okpella masquerade celebrates the harvest and funerals. It also honors special guardian spirits who protect the village. The lead character in the masquerade wears a brightly colored costume and fancy headdress and is called Ancient Mother (Odogu). She dances with a child called Little One (Okeke). This masquerade is about opposites. Ancient Mother is wise, wealthy and beautiful. Idu, the bush monster, is ugly and mean and has crooked teeth and jutting horns. |

|

Ancient Mother (Odogu) headdress and costume |

Ancient Mother and child masqueraders |

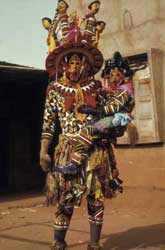

Dodo masquerade, Burkina Faso The Dodo masquerade is performed during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. On the night of the full moon, masqueraders travel from house to house, singing and dancing in return for gifts of money. The mask is made from a dried gourd with horns made of palm stalks and is brightly painted. Older boys sometimes paint their bodies with white stripes and dots.The masquerade tells the story of a hunter who is turned into a monster and banished to the forest when he breaks a promise to his friend. Every group of children performs the songs and dances differently and wears different costumes. Some kids even dress up like airplanes or cars, and others paint famous singers' names on their bodies. Girls also take part in Dodo masquerades as musicians, singers and dancers. In the capital city of Ougadougou, the masqueraders come from many ethnic and religious backgrounds. It is fun to make masks and perform together with kids from different cultures. The government sponsors an annual Dodo competition, and every year boys hope to receive prizes for the best performances and masks. |

|

These boys made their costumes with painted cardboard, raffia and ankle bells. The painted sticks represent the front legs of a wild animal. They are sometimes banged together to sound out a rhythm. |

Members of a Dodo group prepare for their performance. |

|

Carnival, Guinea-Bissau Although Carnival started as a Catholic religious festival in Guinea Bissau, it is now celebrated by boys and girls of all ages and religions. For several days, the streets of Bissau are filled with colorful parades of children and adults dressed as monsters and ghouls, television and cartoon characters and famous people. Some costumes are designed to teach people about topics like equality and HIV/AIDS prevention.It takes teamwork to make a carnival mask. Boys from different neighborhoods put aside differences to form mask-making groups and work on a fun project for a common goal. Even the government gets involved by sponsoring annual parades and competitions for the best mask. |

|

Boys cover a clay model with papier-mâché before painting the mask with bright colors. |

Mask performance at Carnival |

|

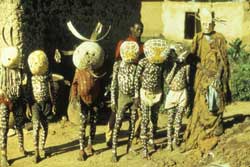

Kuba peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo There are many types of masks in Kuba society. Their meanings, importance and functions vary. Young children are not allowed to view the most important masks. Masks of lesser importance are performed by younger members of the community and surrounded by boys who sing the masks' praises.Kuba children are fascinated by masked performances. After the adults perform, children perform their own masquerades to amuse other children and adults. The children often imitate the adult performance. Kuba men teach their sons to make masks and costumes because the boys will one day be members of the adult masking society. |

|

This mask called Inuba represents a spirit and a chief. It performs at the funerals of community leaders. The boy painted an old water container made from a gourd to create his mask. |

This mask called Inuba represents a spirit and a chief. It performs at the funerals of community leaders. The boy painted an old water container made from a gourd to create his mask. |

|

Yoruba peoples, Masquerades are very important in Yoruba culture. Parents encourage children to participate in the many festivals that are held during the year. The adults coach the children and help them learn to make costumes and dance. Even very small boys perform with the help of their fathers, mothers or other older relatives. |

|

|

Egungun |

African children are encouraged to imitate the gestures and dances of adult masquerades. |

|

Gelede |

Ketu-Yoruba peoples, Idahin, Nigeria |

|

Fante peoples, Ghana Young boys, their fathers and other male relatives perform the Fancy Dress masquerade at Easter, Christmas and the New Year. They wear store-bought masks or make them from wire screen that has been molded to fit the face and then painted. The dancers add hats, gloves or other garments to make each costume unique.The characters in Fancy Dress include an old man, a ship captain, a stilt dancer and animals like the cow, goat, turkey and duck. Fancy Dress costumes, dances and brass-band music are all borrowed from European styles of the 1700s and 1800s. This masquerade may have been brought to Africa by the Dutch, who came to what is now Ghana in 1637. Or it may have come from Caribbean Carnival, which was brought to Liberia and Sierra Leone by freed slaves returning to Africa. |

|

Fancy Dress masquerade |

Fancy Dress masquerade |